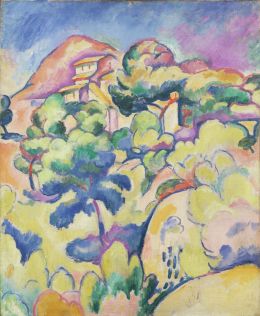

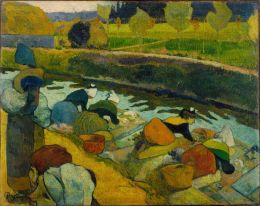

Edward Hopper was born in Nyack, New York, a town located on the west side of the Hudson River, to a middle-class family that encouraged his artistic abilities. After graduating from high school, he studied briefly at the Correspondence School of Illustrating in New York City (1899–1900), and then he enrolled in classes at the New York School of Art (1900–1906). In his shift from illustration to the fine arts, he studied with William Merritt Chase, a leading American Impressionist painter, and with Robert Henri, who exhorted his students to paint the everyday conditions of their own world in a realistic manner. His classmates at the school included George Bellows, Guy Pène du Bois, and Rockwell Kent. After working as an illustrator for a short time, Hopper made three trips abroad: first to Paris and various locations across Europe (1906–7), a second trip to Paris (1909), and a short visit to Paris and Spain the following year (1910). Although he had little interest in the vanguard developments of Fauvism or Cubism, he developed an enduring attachment to the work of Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, whose compositional devices and depictions of modern urban life would influence him for years to come.

In the 1910s, Hopper struggled for recognition. He exhibited his work in a variety of group shows in New York, including the Exhibition of Independent Artists (1910) and the famous Armory Show of 1913, in which he was represented by a painting titled Sailing (1911; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh). Although he worked primarily in oil painting, he also mastered the medium of etching, which brought him more immediate success in sales (25.31.7). He began living in Greenwich Village, where he would continue to maintain a studio throughout his career, and he adopted a lifelong pattern of spending the summers in New England. In 1920, at the age of thirty-seven, he received his first one-person exhibition. The Whitney Studio Club, recently founded by the heiress and arts patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, showed sixteen of his paintings. Although nothing was sold from the exhibition, it was a symbolic milestone in Hopper’s career.

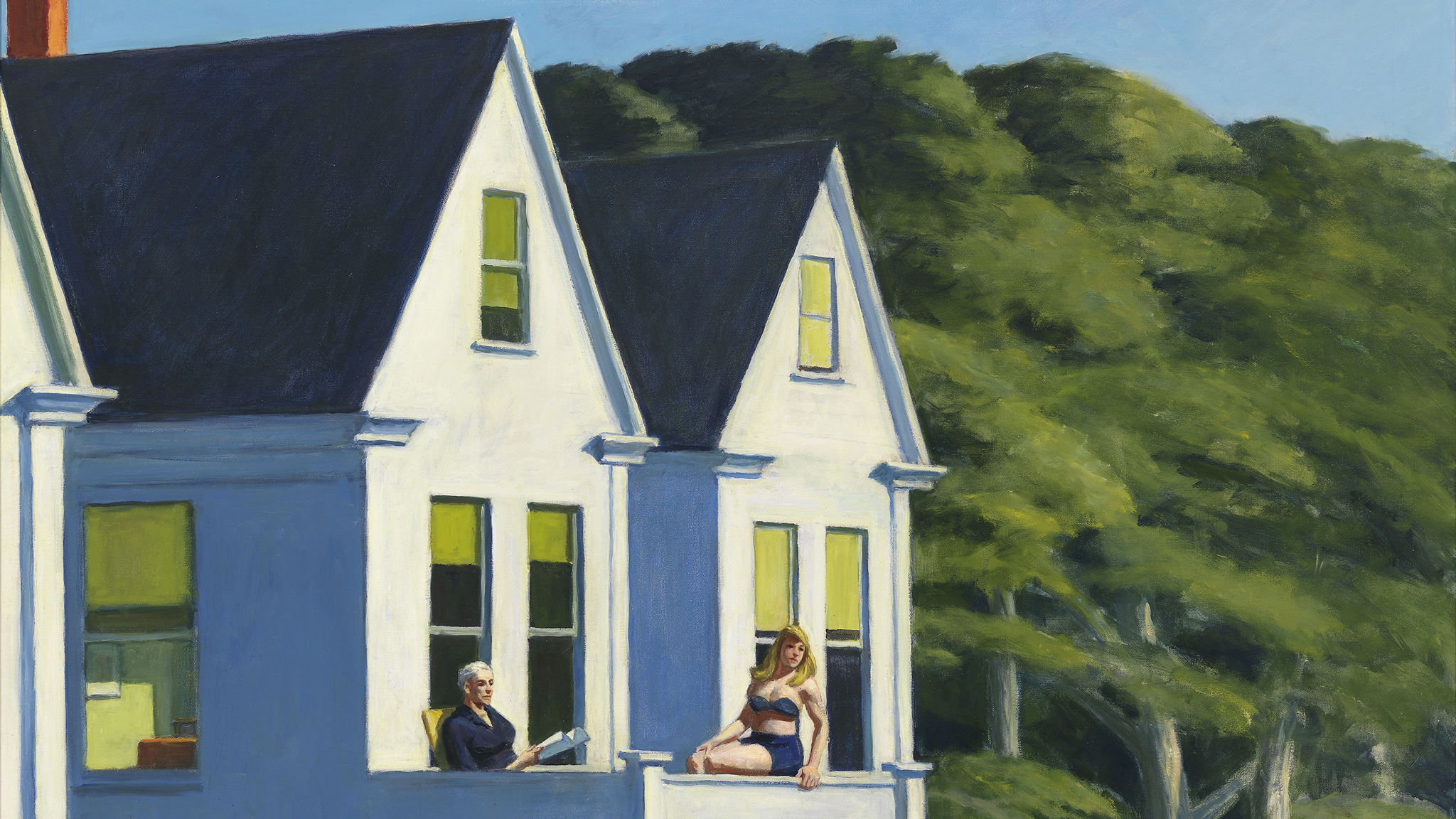

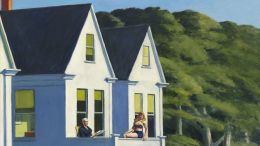

Just a few years later, Hopper found himself in a far more prosperous and prominent position as an artist. His second one-person exhibition, at the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries in New York, was such a commercial success that every painting was sold; the Rehn Galleries represented him for the rest of his career. In 1930, his painting House by the Railroad (1925; Museum of Modern Art, New York) was the first work to be acquired for the collections of the newly founded Museum of Modern Art. This image embodied the characteristics of Hopper’s style: clearly outlined forms in strongly defined lighting, a cropped composition with an almost “cinematic” viewpoint, and a mood of eerie stillness. Meanwhile, Hopper’s personal life had also advanced: in 1923, he married the artist Josephine Verstille Nivison, who had been a fellow student in Robert Henri’s class. Jo, as Hopper called her, would become an indispensable element of his art. She posed for nearly all of his female figures and assisted him with arranging the props and settings of his studio sessions; she also encouraged him to work more extensively in the medium of watercolor painting, and kept meticulous records of his completed works, exhibitions, and sales.

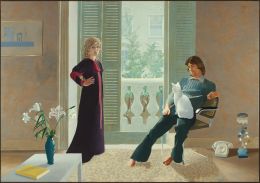

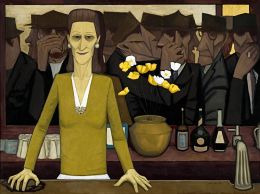

In 1933, Hopper received further critical recognition as the subject of a retrospective exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art. He was by then celebrated for his highly identifiable mature style, in which urban settings, New England landscapes, and interiors are all pervaded by a sense of silence and estrangement (25.31.2). His chosen locations are often vacant of human activity, and they frequently imply the transitory nature of contemporary life. At deserted gas stations, railroad tracks, and bridges, the idea of travel is fraught with loneliness and mystery (37.44). Other scenes are inhabited only by a single pensive figure or by a pair of figures who seem not to communicate with one another. These people are rarely represented in their own homes; instead, they pass time in the temporary shelter of movie theaters, hotel rooms, or restaurants (31.62). In Hopper’s most iconic painting, Nighthawks (1942; Art Institute of Chicago), four customers and a waiter inhabit the brightly lit interior of a city diner at night. They appear lost in their own weariness and private concerns, their disconnection perhaps echoing the wartime anxiety felt by the nation as a whole.

The Hoppers spent nearly every summer from 1930 through the 1950s in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, particularly in the town of Truro, where they built their own house. Hopper used several nearby locations as frequent, repeated subjects in his art (62.95; 1974.356.25). He also began to travel farther for new imagery, to locations ranging from Vermont to Charleston, an automobile trip through the Southwest to California, and four visits to Mexico (45.157.2). Wherever he traveled, however, Hopper sought and explored his chosen themes: the tensions between individuals (particularly men and women), the conflict between tradition and progress in both rural and urban settings, and the moods evoked by various times of day.

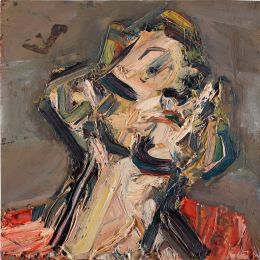

Hopper’s work was showcased in several further retrospective exhibitions throughout his later career, particularly at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; in 1952, he was chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. Despite commercial success and the awards he received in the 1940s and 1950s, Hopper found himself losing critical favor as the school of Abstract Expressionism came to dominate the art world. Even during an era of national prosperity and cultural optimism, moreover, his art continued to suggest that the individual could still suffer a powerful sense of isolation in postwar America (53.183). He never lacked popular appeal, however, and by the time of his death in 1967, Hopper had been reclaimed as a major influence by a new generation of American realist artists.